Born April 4, 1896 - Moinesti, Romania

Died December 25, 1963 - Paris, France

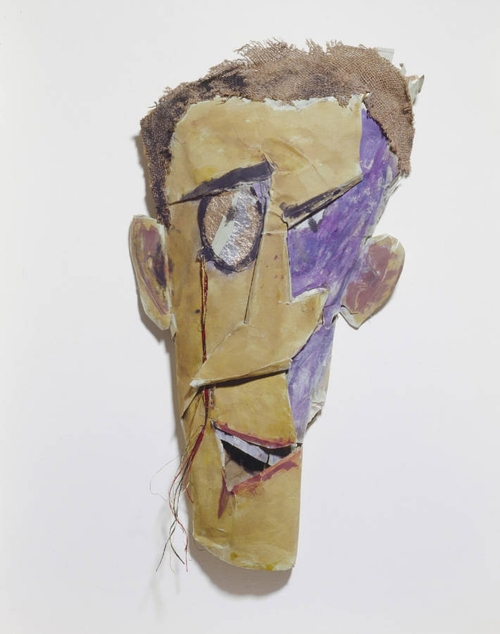

Marcel Janco - Portrait of Tzara -1919

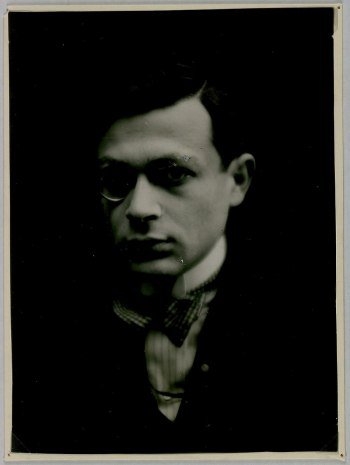

Tristan Tzara in 1922

To Make a Poem

Take a newspaper

Take a pair of scissors

Choose from the paper an article as long as you are planning to make your poem

Cut the article out

Next carefully cut out each of the words that make up the article and put them in a bag

Shake gently

Next take each clipping out one after another in the order in which they left the bag

Copy conscientiously

The poem will look like you

And there you are -- an infinitely original author endowed with a charming sensibility though beyond the understanding of the vulgar.

Tristan Tzara

Website devoted to Tzara

Bilingual interview (3:41 minutes)

Moïcani - L'Odéonie

Tristan Tzara by Man Ray

Poet and tirelessly energetic propagandist for Dada, Tristan Tzara, whose given name was Samuel Rosenstock, was born into a well-off Jewish family in Romania. He attended a French private school in Bucharest as a youth and while in high school met Ion Vinea and Marcel Janco, both of whom shared his interest in French poetry. Together they founded the literary magazine Simbolul, in which Tzara, under the pseudonym S. Samyro, published a selection of poems written in Romanian and influenced by French symbolism.

In 1915, seemingly as the result of a family scandal, Tzara's parents sent him to Zurich, where he enrolled at a university to study philosophy. His first poem signed with the name Tristan Tzara (tzara being the Romanian for land) appeared in October of that year. Romania did not enter the war until 1916, but it is not clear when Tzara might have been first drafted for service. In the fall of 1916 he received papers granting him a deferral of military service, and in 1917 he was relieved from military duty.

Shortly after his arrival in Zurich, Tzara reunited with Janco and Janco's brother Georges, with whom, according to Hugo Ball's diary, he attended the opening night of the Cabaret Voltaire. Over the course of the year in 1916, Tzara's activities at the Cabaret of reciting his poems and those of others led to a more active role in coordinating and planning Dada events. He also, probably through the influence of Richard Huelsenbeck, became interested in African poetry. He incorporated into his poetry scraps of sound, bits of newspaper fragments, and phrases resembling African dialects. Beginning in November 1916, Tzara collected and translated African and Oceanic poems from anthropology magazines in the Zurich library. The soirées nègres at the Cabaret Voltaire led to Tzara's lifelong collecting of African and Oceanic art. On July 23, 1918, in Zurich's Meise Hall, Tzara recited his "Manifeste Dada 1918." Also published in Dada 3, this radical dadaist declaration reached André Breton in Paris, thus beginning the connection that would bring Tzara and Dada to Paris a year later. It was through Tzara's efforts that Dada in Zurich reached a broad international audience, and he has often been described as embodying the migratory quality of Dada.

Tzara arrived in Paris and burst upon the avant-garde literary scene in 1920 at a poetry reading organized by Littérature. He brought to Dada in Paris a skill in managing events and audiences, which transformed literary gatherings into public performances that generated enormous publicity. He remained the editor of Dada, which appeared in France until 1922. As the cohesiveness of the Dada movement in Paris was disintegrating, Tzara published Le Coeur à barbe (The Bearded Heart), a journal reacting against Breton and Francis Picabia.

From 1930 to 1935, Tzara contributed to the definition of surrealist activities and ideology. He was also an active communist sympathizer and was a member of the Resistance during the German occupation of Paris. Tzara remained a spokesman for Dada, and in 1950 delivered a series of nine radio addresses to his Parisian audience discussing the topic of "the avant-garde revues in the origin of the new poetry." In 1962 Tzara traveled for the first time to Africa. He died in Paris the next year.

Jeffrey Shivar

Le Coeur à Barbe

Journal transparent. Gérant: G. Ribemont-Dessaignes. No. 1, avril 1922. (8) pp., printed on pale pink stock. Texts by Duchamp ("Rrose Sélavy"), Éluard, Fraenkel, Huidobro, Josephson, Péret, Ribemont-Dessaignes, Satie, Serner, Soupault and Tzara. A counterattack launched by Tzara following Picabia's insulting La Pomme de pins of the previous month; one more missile hurled during the spring of 1922, which Breton was later to comment witnessed the "obsequies of Dada." The cover design is one of the best-known and most appealing graphic inventions of Paris Dada; in the National Gallery of Art Dada catalogue (2006), it is attributed to Iliazd.

Paris (Au Sans Pareil), 1922.

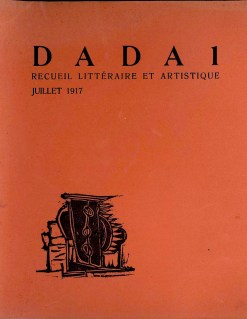

Dada n° 1 - July 1917 (wholly restored full-text download)

"Manifestation Dada" in Dada n° 7 Dadaphone - March 1920

Dada n° 7 Dadaphone. Editor: Tristan Tzara. (8) pages, 10 illustrations (halftone photographs). Front cover design by Picabia. Contributions by Tzara, Picabia ("Manifeste Cannibale Dada"), Breton, Éluard, Ribemont-Dessaignes, Soupault, Cocteau, Dermée, Aragon, Arnauld, Evola and others. The penultimate issue of Dada, brought out by Tzara in March 1920, at a moment of inspired Dada activity in Paris, just before the Manifestation Dada at the Maison de l'Oeuvre (March 27), the first appearance of Cannibale (April), the Festival Dada at the Salle Gaveau (May).

Reminiscent of 391 and with a strong Parisian bias along Littérature lines (like Dada 6), Dadaphone's visual interest is mostly in its insistent typographic density, rather than its illustration--though it does include a beautiful abstract Schadograph, purporting to show Arp and Serner in the Royal Crocodarium in London, as well as the spiralingly zany

Picabia drawing on the front cover. It includes an example of the broadside "Manifestation Dada," designed by Tristan Tzara, originally stapled in the middle of the issue, as is sometimes found. A great succès de scandale, the Manifestation Dada was the third, and most elaborate, of three Dada demonstrations after the arrival of Tzara in Paris, precipitating plans for the Festival Dada. This broadside handbill, printed on pink stock, with red mechanomorphic line drawings by Picabia superimposed over the text, is one of the best ephemera of Paris Dada, and among the rarest. In addition to providing a complete program of the performances (works by Dermée, Ribemont-Dessaignes, Picabia, Aragon, Breton and Soupault, Éluard, Tzara and others), it carries advertisements for the forthcoming Dadaphone, 391 no. 12, and Proverbe, printed sideways at the right edge, printed in red.Oblong sm. folio. 266 x 373 mm. (10 7/16 x 14 11/16 inches).

Paris (Au Sans Pareil), 1920. Estimated at $9,500.00

Ars Libri Ltd. | 500 Harrison Avenue | Boston | MA | 02118

Ernest Hemingway by Man Ray

From Ernest Hemingway's The Snows of Kilimanjaro

"Later he had seen the things he could never think of and later still he had seen much worse. So when he got back to Paris that time he could not talk about it or stand to have it mentioned. And there in the café as he passed was that American poet with a pile of saucers in front of him and a stupid look on his potato face talking about the Dada movement with a Roumanian who said his name was Tristan Tzara, who always wore a monocle and had a headache..."

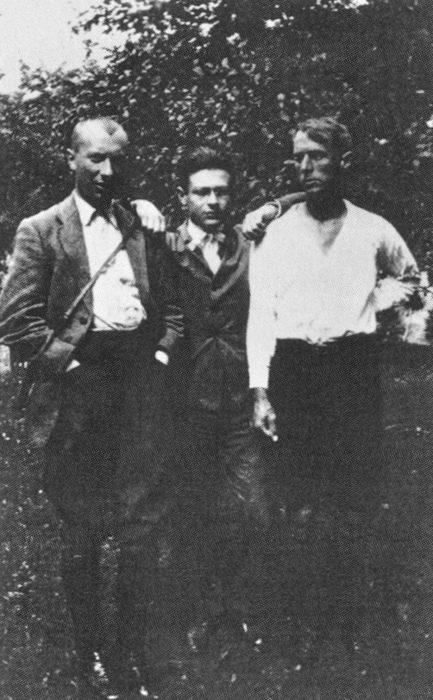

Hans Arp, Tristan Tzara and Max Ernst in 1921

To read excerpts of Tzara's explanation of Dadaism taken from his "Dada Manifesto" [1918] and "Lecture on Dada" [1922], translated from the French by Robert Motherwell in his Dada Painters and Poets, New York, pp. 78- 9, 81, 246-51; reprinted by permission of George Wittenborn, Inc.

See: http://www.sas.upenn.edu/~jenglish/English104/tzara.html

Tristan Tzara: "Dadaism" - Dada Manifesto 1918

The Dada Manifesto in English

Tzara as a young man

Tristan Tzara (1896-1963)

Vidéo YouTube without subtitles, unfortunately, on his life in Dada. A good collection of photos.

Music: Henri Sauguet (1901-1989), Piano Concerto n° 1.

Dialogue Richard Huelsenbeck - Tristan Tzara

between the two in English and French on the subject of the beginning of Dada in Zurich. Fascinating and essential!

On YouTube.